Andersons Querzahnmolch

Ambystoma andersoni

Andersons Querzahnmolch

Ambystoma andersoni

Zielvorgabe CC

40 Haltende

Stand 11/2025

Zielvorgabe CC

225 Tiere

Stand 11/2025

Zielvorgabe CC

40 Haltende

Stand 11/2025

Zielvorgabe CC

225 Tiere

Stand 11/2025

Was würden Sie denn machen, wenn Sie es in Ihrem Zuhause so richtig schön wohnlich und gemütlich haben, das Wetter draußen aber immer unfreundlicher und schließlich kaum noch zu ertragen ist? Genau: Man bleibt lieber da, wo man ist. Da würde man doch keinen Hund vor die Tür jagen, heißt es. Warum dann aber einen Lurch?

Salamanderfeindliches Klima

Exakt dieses Draußen-Dilemma stellte sich den Querzahnsalamandern im Hochland von Mexiko vor langer Zeit. Das Klima wurde immer trockener, die Salamander aber mögen es feucht. Als Larven leben sie im Wasser, wo nach wie vor alles zum Besten stand. Nach dem Landgang aber krochen sie in eine zunehmend salamanderfeindliche Umgebung. Da erscheint es nur konsequent, dass sie das irgendwann einfach sein ließen und ganz im Wasser blieben.

„Ewige Jugend“ bei Schwanzlurchen

Lake, sweet Lake

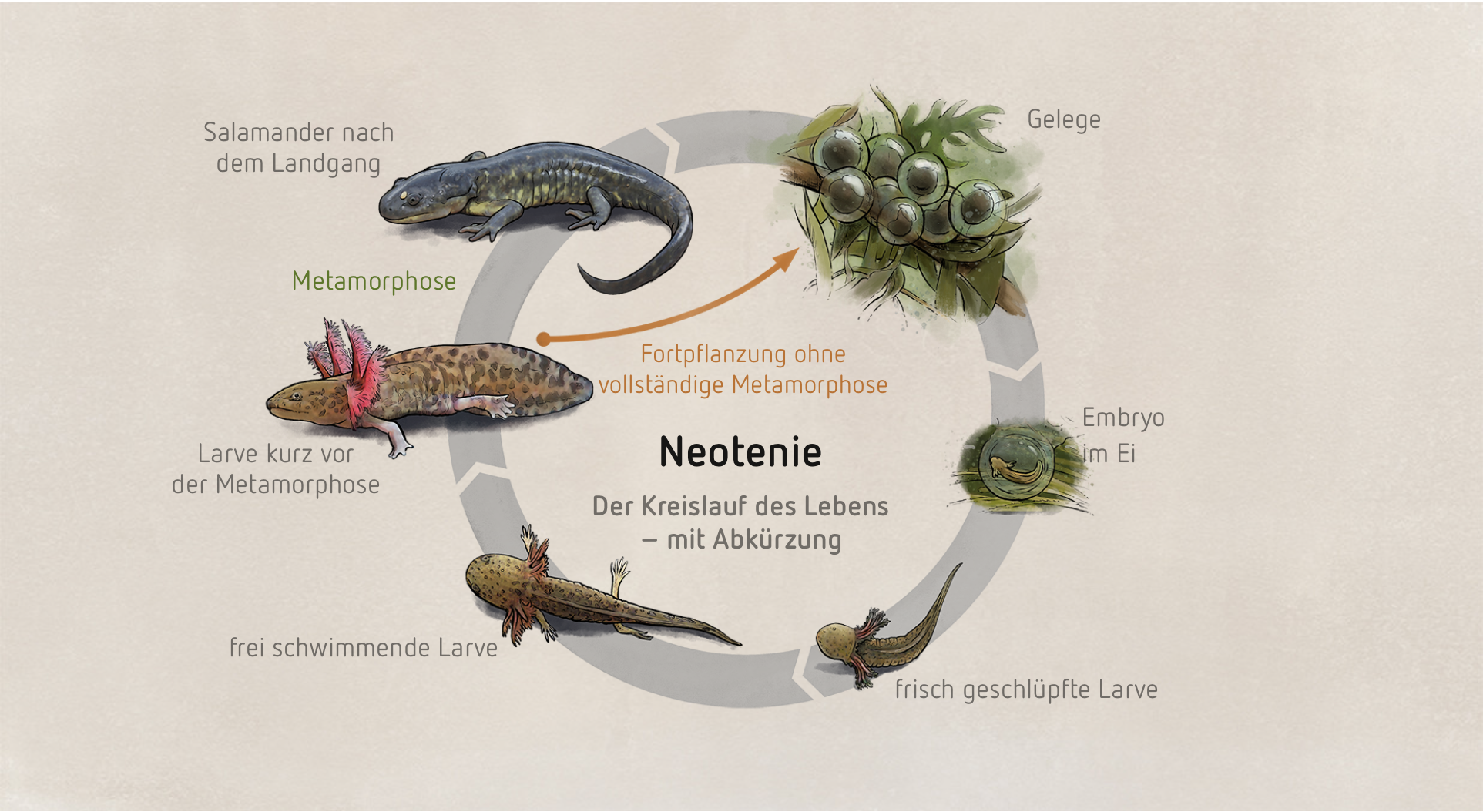

Natürlich kann ein Salamander nicht entscheiden, ob er nach seiner Zeit als im Wasser lebende Larve die Metamorphose durchläuft und an Land geht oder eben nicht. Aber tief in ihren Genen haben viele Schwanzlurche die Option gespeichert, die Metamorphose nicht vollständig zu durchlaufen und auch als erwachsene Tiere im Wasser zu leben. Die geschlechtsreifen Tiere behalten dann einige Larvenmerkmale bei, etwa die Außenkiemen, mit denen sie unter Wasser atmen können. Neotenie nennt man dieses Phänomen, und das weltweit bekannteste Beispiel dafür ist ein naher Verwandter von Andersons Querzahnmolch: der Axolotl. Wenn der Verbleib im Wasser einen Überlebensvorteil mit sich bringt, sorgen letztlich die evolutionären Mechanismen dafür, dass irgendwann die ganze Population ein Leben lang in dem See bleibt, der ursprünglich nur ihre Kinderstube war.

Querzahnmolche – doppelt divers

Inseln unter Wasser

So wurden die landbewohnenden Querzahnsalamander im Hochland von Mexiko also nach und nach zu wasserlebenden Querzahnmolchen, die in den verschiedenen Seen der Region mit ihren Zu- und Abflüssen herumschwammen. Und prompt schlug die Evolution erneut zu, diesmal mit dem berühmten Insel-Effekt. Da die verschiedenen Seen räumlich voneinander getrennt sind und deshalb die in ihnen lebenden Molche keinen Kontakt mehr miteinander hatten, entwickelten sie im Lauf der Jahrmillionen eigene Merkmale, durch zufällige Mutationen oder spezielle Anpassungen an ihre Umwelt. Irgendwann hatten sie so unterschiedliche Wege eingeschlagen, dass sie zu eigenen Arten geworden waren – ein Musterbeispiel für die Entstehung von Biodiversität.

Andersons Querzahnmolch lebt ausschließlich in der Laguna Zacapu, ein kleiner See mit einer Fläche von weniger als 40 Hektar.

Laguna de Zacapu © Joachim Nerz

Dem Molch geht‘s an die Kiemen

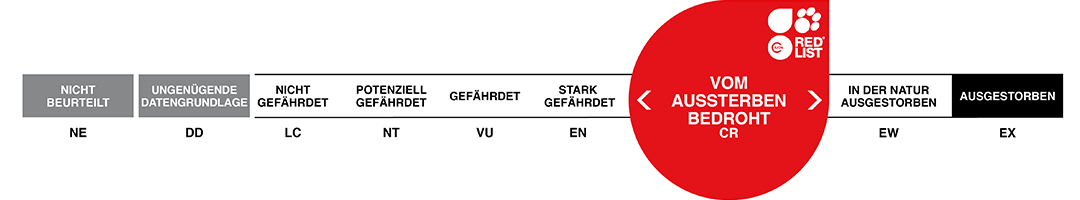

Andersons Querzahnmolch lebt ausschließlich in der Laguna de Zacapu, ein kleiner See mit einer Fläche von weniger als 40 Hektar. Ein gut isolierter, winziger Lebensraum und zugleich ein Laboratorium der Artenbildung. Neben Andersons Querzahnmolch gibt es auch noch mehrere nur dort vorkommende Fisch- und Krebsarten. Allerdings liegt der See direkt an der 50.000-Einwohner-Stadt Zacapu, er ist sozusagen ihr Stadtteich. In der Umgebung wird Landwirtschaft betrieben. Beides führt zu einer erheblichen Wasserverschmutzung und -verschlammung, was den Molchen stark zusetzt. Außerdem galten die mit 28 cm Länge recht stattlichen Tiere schon immer als Leckerbissen, weshalb sie befischt wurden und wohl trotz Unterschutzstellung auch immer noch werden. Ausweichen können die Lurche nicht – die Weltnaturschutzunion IUCN schätzt sie deshalb in der höchsten Bedrohungskategorie für wild lebende Arten als akut „vom Aussterben bedroht“ ein.

The Circle of Life: Die „normale“ Salamanderentwicklung verläuft von Eiern, in denen sich die Larven entwickeln, die meist beinlos schlüpfen, dann Gliedmaßen entwickeln, heranwachsen und schließlich eine Metamorphose durchlaufen. Die umgewandelten Tiere leben dann an Land, bis sie selbst zur Fortpflanzung schreiten. Neotene Salamander nehmen im Wasser eine Abkürzung: Sie durchlaufen die Metamorphose nur teilweise, bleiben im Wasser und sind als „Dauerlarven“ dennoch geschlechtsreif. © Jonas Lieberknecht

Schafft zwei, drei, viele Seen

Im Grunde ist so ein kleiner See auch nur ein großes Aquarium. Nur ist es leider derzeit defekt, und eine Reparatur ist zwar grundsätzlich möglich, erfordert aber viel Zeit, Kosten und Mühen. Bislang ist mit den Arbeiten dazu noch nicht einmal ernsthaft begonnen worden. Es ist daher wahrscheinlich, dass Rettungsmaßnahmen vor Ort für Andersons Querzahnmolch zu spät kommen. Er wird womöglich bald aussterben in der Laguna de Zacapu. Deshalb will Citizen Conservation dazu beitragen, den Tieren ersatzweise andere, funktionstüchtige Aquarien zur Verfügung zu stellen – in Zoos und bei privaten Lurchfreundinnen und -freunden. Denn die Haltung und Zucht dieser Amphibien ist gut möglich, an sich ist Andersons Querzahnmolch ziemlich genügsam. Wenn genug Leute mitmachen, können wir ihm so lange in menschlicher Obhut Asyl bieten, bis eines Tages hoffentlich auch sein heimatlicher See wieder amphibienfreundlich hergerichtet worden ist. Und es wäre doch ein Jammer, wenn es diese Kleinode der Evolution dann nicht mehr geben würde. So werden Sie CC-Halter oder -Halterin.

Für Haltende

Basisinformationen zu Biologie und Haltung

Haltung im Aquarium mit Filter, ab 200 Liter für ein Pärchen. Gruppenhaltung möglich. Die Wassertemperatur sollte im Jahresverlauf zwischen 16 und 20 °C schwanken, 22 °C werden temporär vertragen, 24 °C und mehr müssen vermieden werden. pH-Wert 6,8–8,2, Härte 4–5° dH. Bodengrund Sand oder Kies unter 3 mm Körnung. Versteckplätze und Wasserpflanzen. Ernährung mit Low-Protein-Pellets, Mückenlarven, Wirbellosen, Fischen u. Ä.