With God’s help for the toads

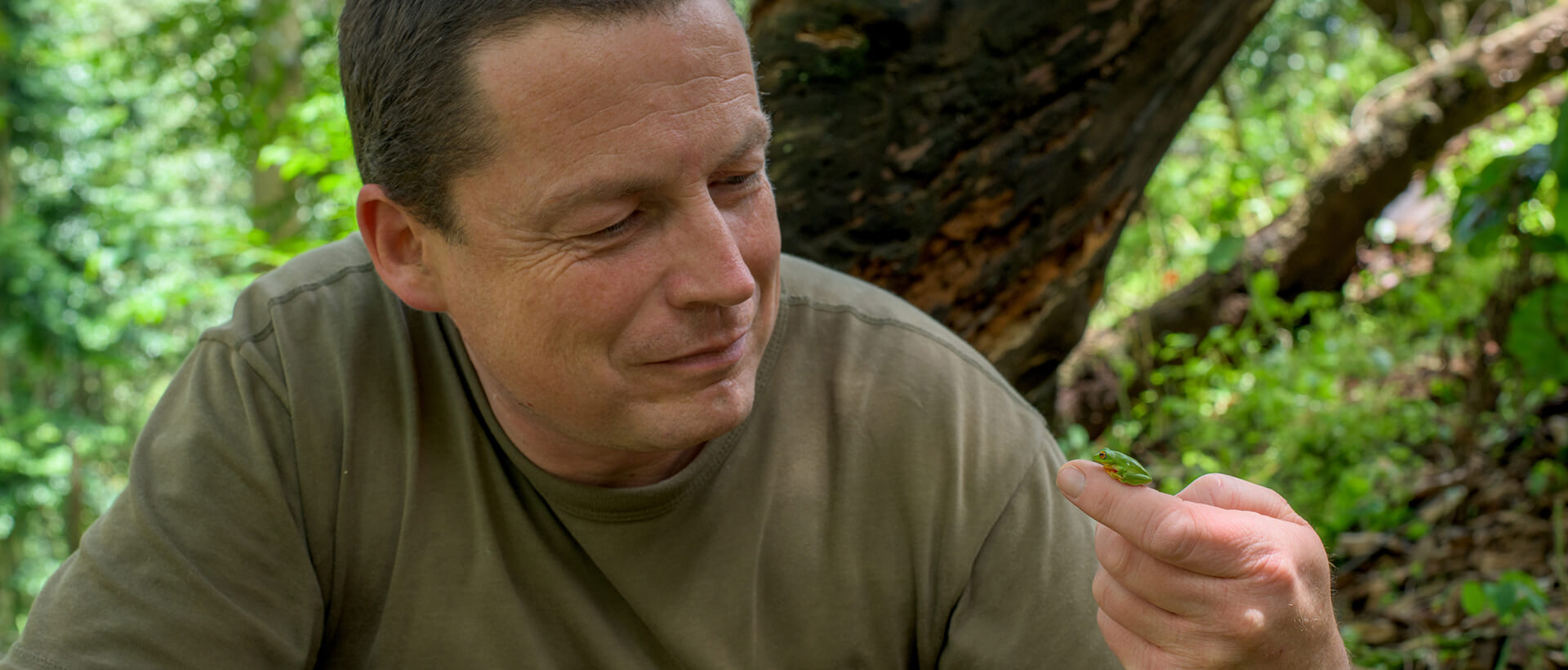

How on earth did a pastor and teacher go to the frogs? Actually, he had wanted to become a biologist. Because of his passion for animals. It must have been in 1974 when five-year-old Ole was waiting at the dentist’s office and, tormented by boredom, picked up one of the picture books on display. It was about amphibians, the development from egg to tadpole to the finished amphibian, about the biggest and the smallest frog in the world. The boy was immediately enthusiastic, it was a love at first sight that would not let him go. Perhaps it was God’s providence. In the end, he studied Protestant theology, but as an enthusiastic nature photographer, he continued to devote his free time to frogs. An educational path from pastor to toad protector!

From nature photographer to amphibian breeder

Schon als Kind schleppte Ole allerlei Getier nach Hause, fasziniert saß er vor dem Fernseher, wenn Sielmann und Professor Grzimek die Zuschauer mitnahmen auf ihre Expeditionen ins Reich der wilden Tiere, und die Schülerzeitschrift „Tierfreund“ ließ ihn staunend die Bilder renommierter Fotografen betrachten – das weckte den Wunsch, selbst Tiere zu fotografieren. Mit dem ersten durch Schülerjobs selbst verdienten Geld kaufte er sich eine gute Kamera, und los ging´s! Doch viele Amphibien ließen sich in allen ihren Verhaltensweisen nur schwer in freier Natur dokumentieren. So kam Ole zur Terraristik.

Ole's favorite photo subjects

The Western Ghats in India are a hotspot of amphibian diversity. Here, amateur nature photographer Ole Dost finds plenty of photo motifs during his excursions, such as the Asian black-spined toad (Duttaphryne melanostictus), which is widespread in South Asia. | Ole Dost

Ghaticxalus asterops is the most strikingly colored member of its small frog genus, found only in the Western Ghats. | Ole Dost

Among the least known amphibians are the subterranean caecilians. Only during heavy rainfall does Ichtyophis kodaguensis dare to come to the surface. | Ole Dost

Die Gattung Indosylvirana kommt fast ausschließlich in den Western Ghats vor. Indosylvirana sreeni lebt am Rand von Gewässern und ist immer bereit, mit einem beherzten Sprung ins rettende Nass einzutauchen. | Ole Dost

For humans, the more than 20 species of the genus Minervarya are hardly distinguishable. And yet each has its own call, and the females of Minervarya mudduraja know exactly that they are expected by this male. | Ole Dost

Wie in allen tropischen Regionen teilt man auch in den Western Ghats seine Unterkunft häufig mit einem sympathischen Badezimmerfrosch. Hier hat Polypedates maculatus sich dieser Rolle angenommen. | Ole Dost

Although the shrub frog Polypedates pseudocruciger belongs to a genus that is widespread and species-rich in South Asia, it is found here exclusively in the Western Ghats. | Ole Dost

In an altitude range between 1,500 and 2,600 meters the characteristic shola forests are growing, evergreen tree groves embedded in grassland. Unfortunately, they have been largely deforested, and with them the Raochrestes chlorosomma, which only lives here, is threatening to disappear. | Ole Dost

Besonders hübsch ist die zweifarbig rot und blau leuchtende Iris von Especially pretty is the bicolor red and blue iris of Raorchestes glandulosus. | Ole Dost

Coffee plants are ideal calling grounds for the reproductively active males of Raochestes jayarami | Ole Dost

The somewhat bulbous Uperodon triangularis lays its eggs in water-filled tree cavities of upland forests. | Ole Dost

It is worth looking deep into the eyes of Raorchestes luteolus, which are usually yellowish orange at mating time - for they are adorned with a fine blue ring. | Ole Dost

Raorchestes sushili also lives in the endangered shola forests. | Ole Dost

The most colorful frog of the Westghats is probably Rhacophorus lateralis. If you get funny with him, he can change his color to a dirty brown. | Ole Dost

The flying frog Rhacophorus malabaricus can cover a distance of over ten meters with its gliding jump | Ole Dost

The call of the wild

In the terrarium, Ole brought nature home to photograph, but photography always brought him into the wild. After years of photographing native species, he was lured by the biodiversity of the rainforests. Looking for a conveniently accessible destination, he came across the little-known Western Ghats mountain range in southern India – a global amphibian hotspot. He was enthralled by the region’s richness of species and individuals, and returned here again and again for new photo safaris.

From a racing bike riding pastor to a toad

With the racing bike to the toad

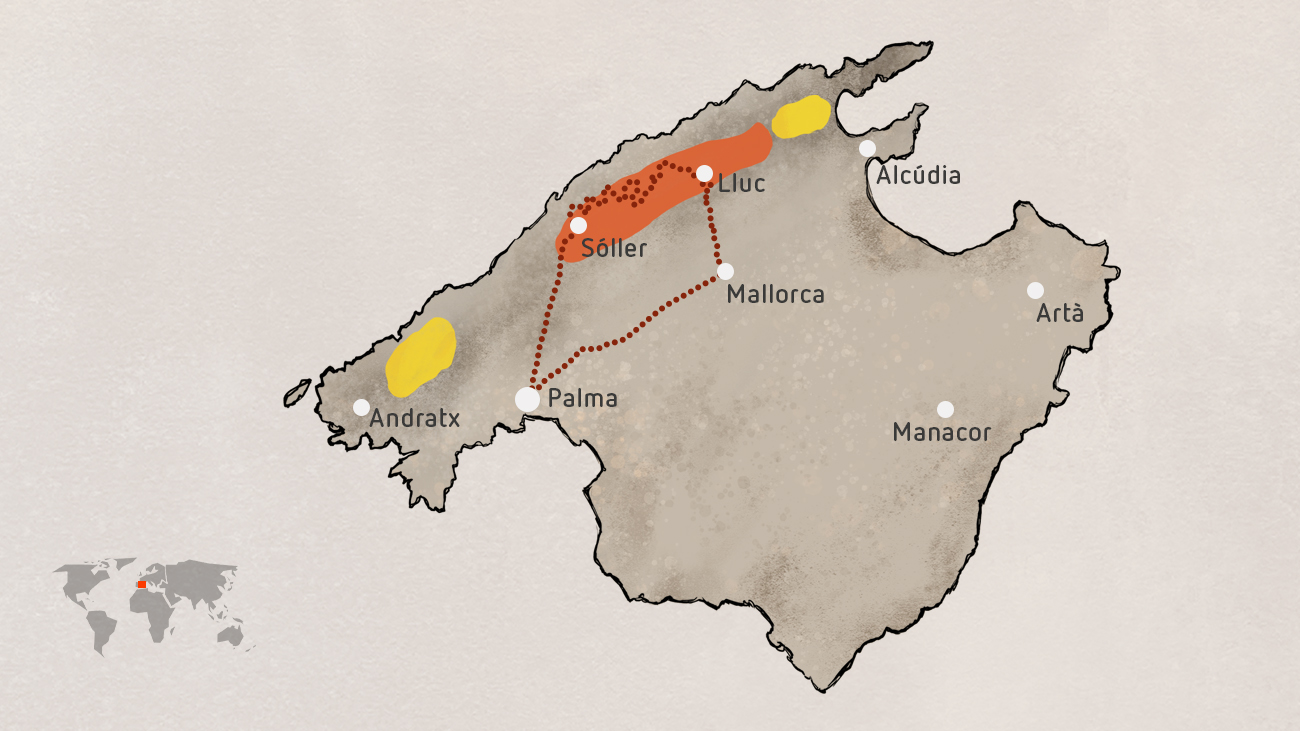

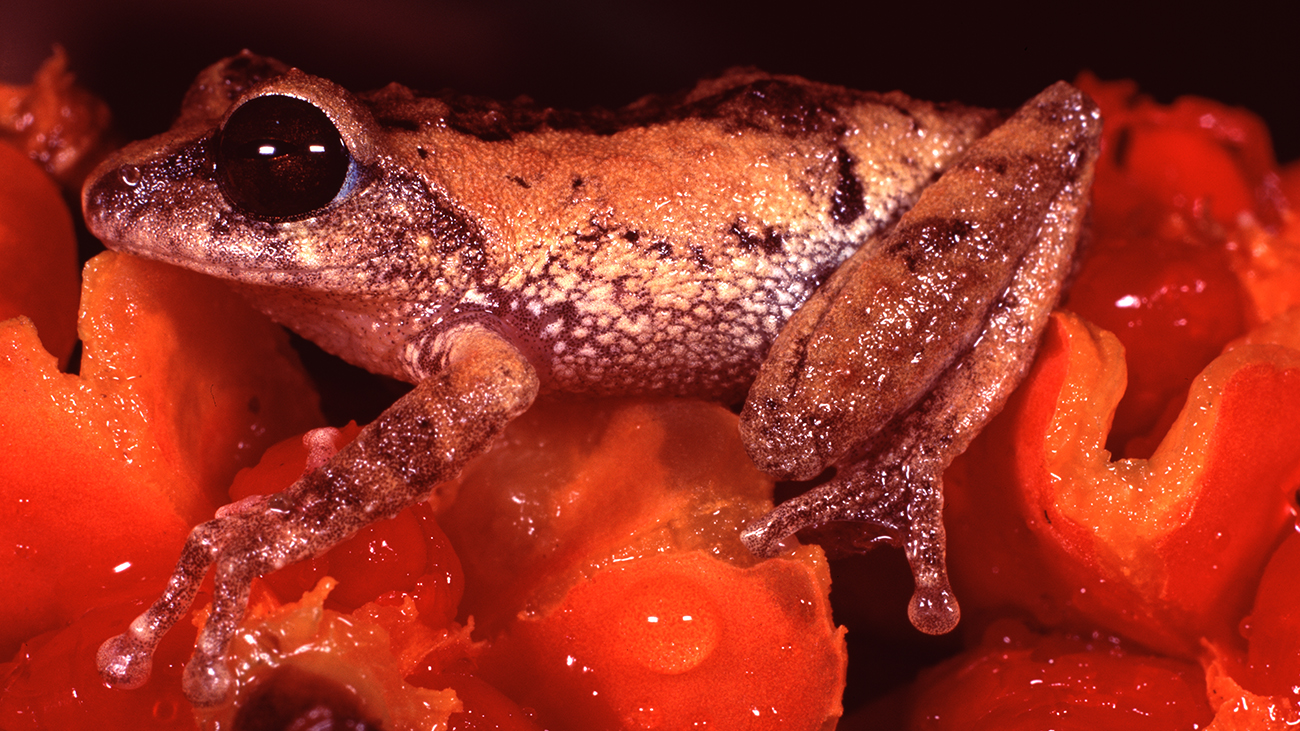

Besides photography, Ole also indulges in road cycling. His home in the Black Forest offers plenty of beautiful routes with decent climbs. He participated in cycling marathons all over Europe. It was also a bike race that took him to Mallorca in the Serra de Tramuntana. Later, he read in a journal that in the ravines there a living fossil has survived to this day: the Mallorca midwife toad. It is critically endangered, but its population has been stabilized through a dedicated zoo breeding program. When Citizen Conservation offered the opportunity for private owners to join this conservation project, Ole was immediately on board.

Enthusiastic about nature

Ole has not only been able to get his own two children excited about amphibians; the biology teachers at his school have also had the clerical colleague design an amphibian course. With great success: “Even the most behaviorally challenged students were captivated by the live frogs on display,” he reports. “Our youth are not supposed to be enthusiastic about nature? Nonsense! What’s crucial here is the personal experience.” That’s another reason he’s a convinced participant in Citizen Conservation. “There I can kill two birds with one stone: commitment to species conservation and arouse enthusiasm in others for these endangered animals!”