Animal population overview 1/2025 – where diversity is still a top priority!

Tags

On International Biodiversity Day on 22 May, Citizen Conservation traditionally presents its own personal biodiversity review in the form of the results of the current population count.

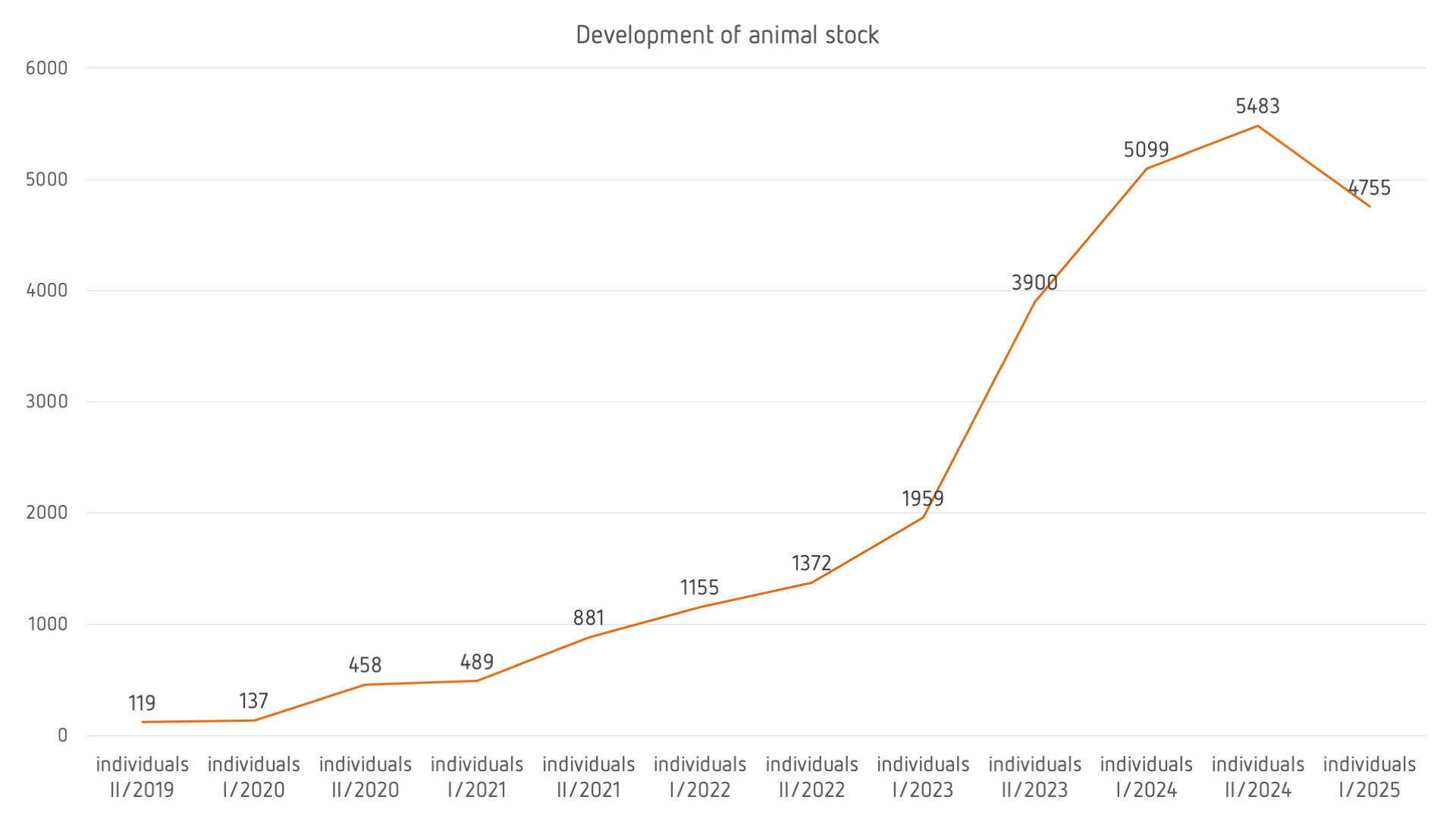

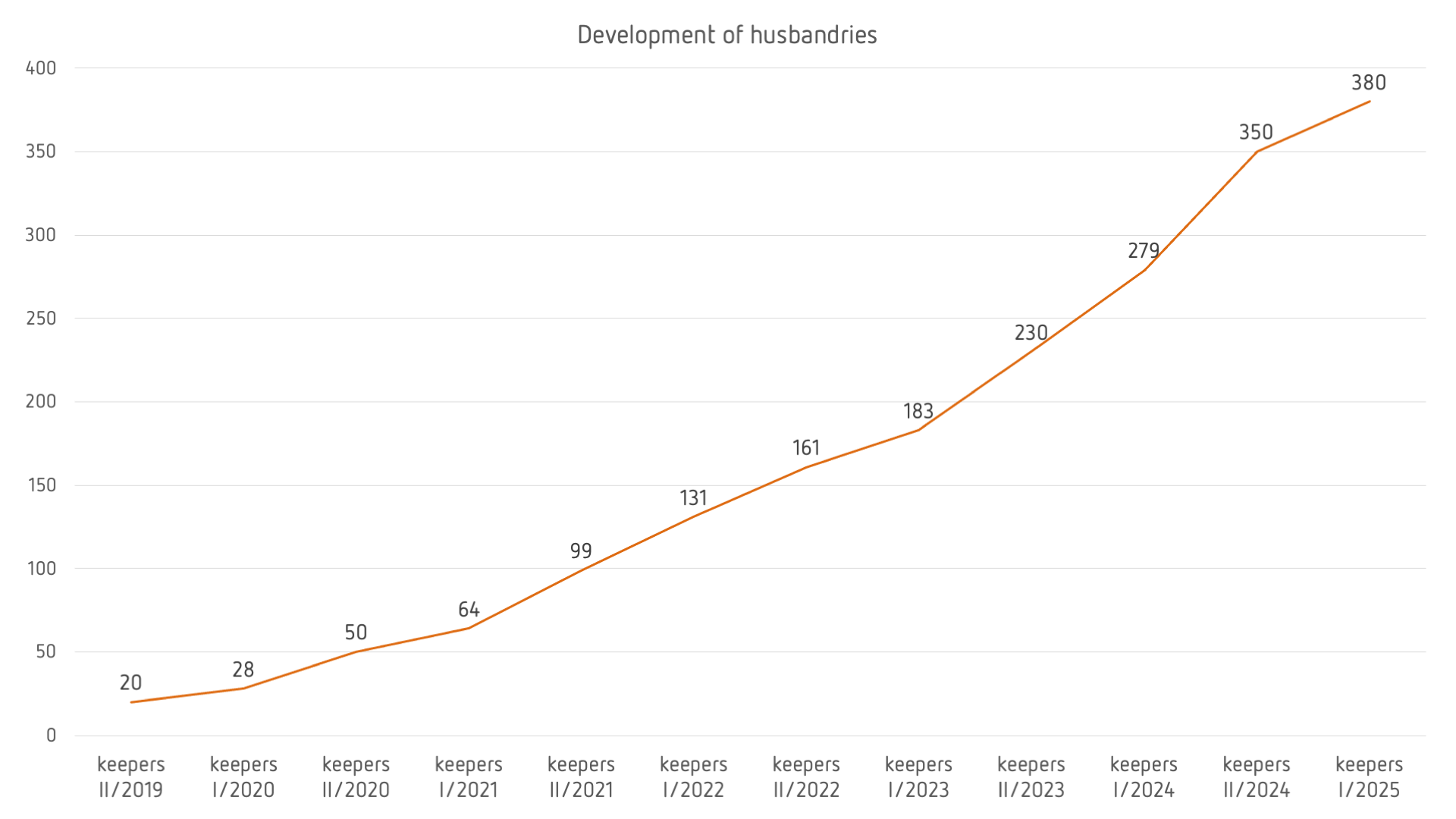

On 1 May 2025, the number of animals under CC’s care was 4,755 individuals. These belong to 31 taxa: 19 amphibian, 7 fish and 5 reptile species. The animals are cared for by 238 keepers in 380 husbandries.

A mirror of civil society

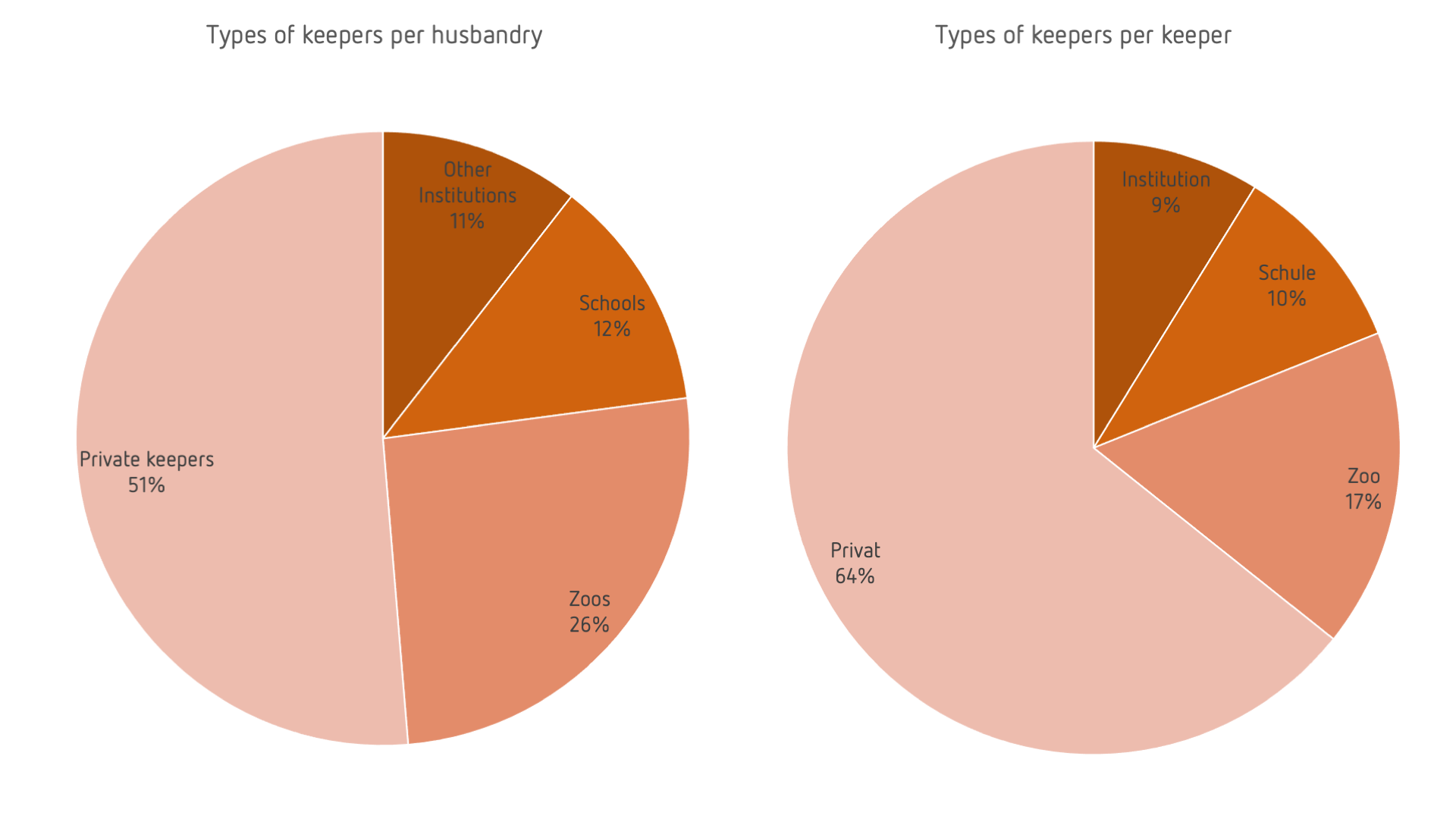

Citizen Conservation is an association of private animal keepers who volunteer to protect species by participating in the conservation breeding of endangered wildlife, as well as institutions such as zoos and other exhibition centres, schools, natural history museums, rescue centres and associations. Around 2/3 of our keepers (64% to be precise) are private individuals, 17% are zoos, 10% are schools and 9% are other institutions. Since institutions take on more species on average, their share of the number of husbandries is larger – 51% are in the hands of private individuals, 26% in zoos, 12% in schools and 11% in other institutions. 328 husbandries are located in Germany, 18 in Switzerland and 14 in Austria. However, CC animals are also kept in Latvia, Poland, Sweden, the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, Hungary, Slovenia and the Czech Republic.

One of the most successful CC programmes protects the Mallorca Midwife Toad. The targeted number of animals and husbandries has been reached, meaning that offspring can now also be distributed.

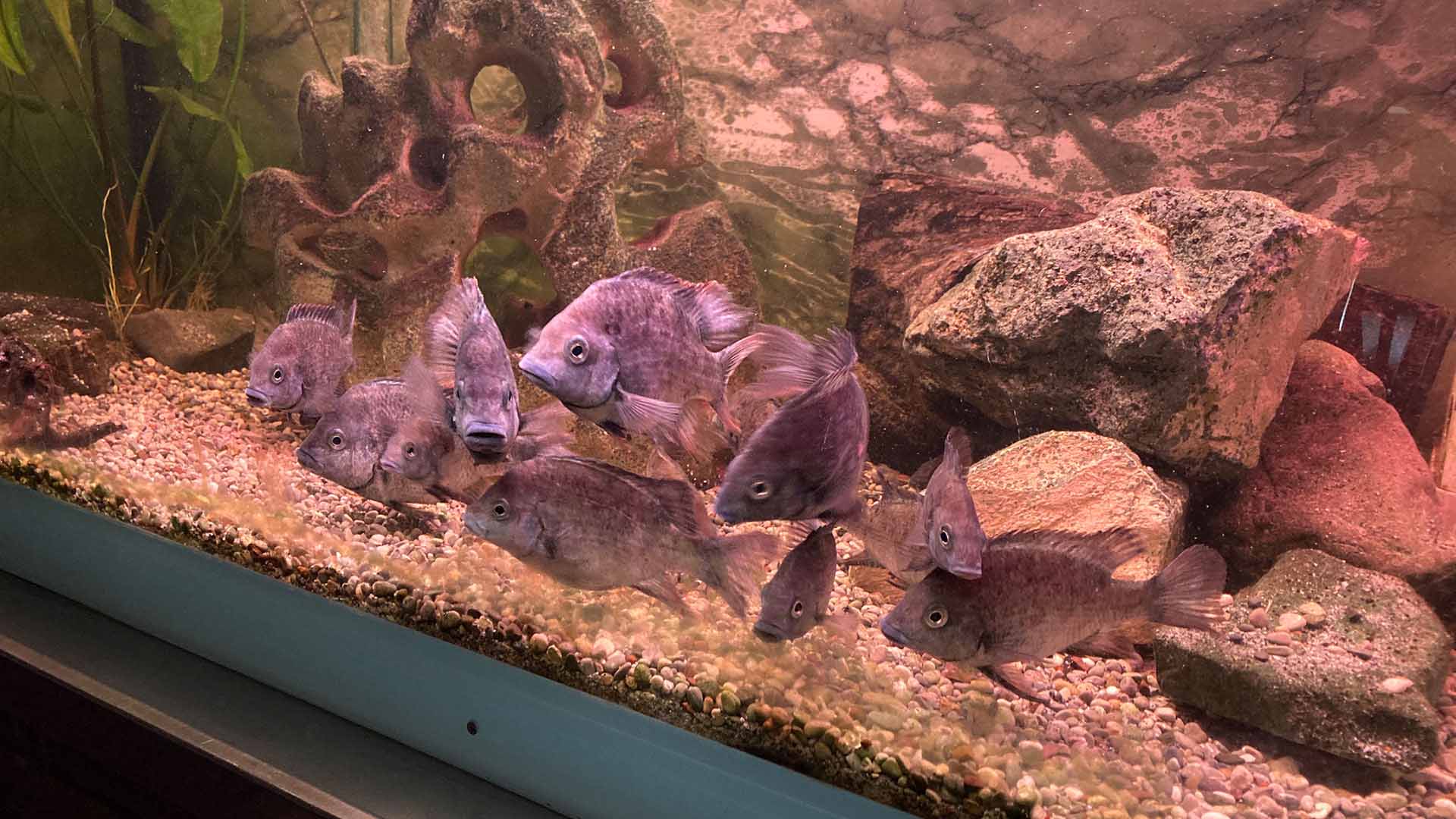

Mangarahara Cichlids produce clutches of 100 or more larvae. The fact that not all of them grow up is part of the species' reproductive strategy.

Welcome to the movement! In May, Golden Poison Frogs moved in with 15-year-old young terrarium keeper Kien in Switzerland, supported by his mum Sandra. Beforehand, Kien had already thoroughly researched the husbandry requirements for his new fosterlings at Zurich Zoo.

The community is getting bigger

These numbers are very encouraging for Citizen Conservation. They show a constant increase in the number of keepers as well as husbandries and an expansion of the movement in Europe. On 1 November 2024, there were 214 keepers. A year ago, on 1 May 2024, there were 175, so we are pleased to report a remarkable increase of 63 new participants within 12 months. This is an increase of 36%. The situation is similar when it comes to the number of husbandries. A year ago there were 279 – so there are exactly 101 new additions in stocks of frogs, salamanders, fish and reptiles. Curiously, this also corresponds to exactly 36% growth.

Many offspring, higher losses

The number of animals, on the other hand, has decreased from 5,483 on 1 November 2024 and 5,099 on 1 May 2024 to the 4,755 on 1 May 2025 mentioned above. How can that be? There are three reasons. Firstly, there are simply uncertainties in the count. In the case of clutches with one hundred, two hundred or more juveniles resulting from them, the time of reporting and the question of when larvae are counted at all already cause considerable differences in the total number. Secondly: If you count even small tadpoles or larvae and include them in the balance, the losses are usually higher. This is because many of our species are so-called r-strategists that produce a lot of offspring in one go, which usually results in a relatively high mortality rate. This is the case with our cichlids, for example, which sometimes produce well over 100 larvae in a single clutch, although there are more frequent losses as they grow. Our harlequin toads follow this strategy too, and the tiny metamorphs are also quite vulnerable. This means that higher losses can hardly be prevented – and yet a pleasingly large number of hatchlings survive.

Marketing for the protection of species

Thirdly, it is part of CC’s concept that we do not keep all animals bred in the programme. The purpose of coordinated conservation breeding is to build up a population that is demographically stable and genetically as diverse as possible. If there are lots of offspring from a single clutch, they would quickly become overrepresented in the population from a genetic point of view. We have also defined goal numbers for our species that indicate how many animals are required to maintain a conservation breeding programme over 40 years. These specific numbers can be found in our stock overview. They are not a dogma, but once they have been reached, we will not aim to further increase the number of animals kept – these capacities can be better utilised for specimens of other endangered species. The surplus animals in CC can therefore be sold. The generated sales income supports the financing of our programmes and thus directly benefits species conservation. As we have now reached our targeted numbers for the Mallorcan Midwife Toad, some of the offspring – 341 animals – were sold in the past six months. Offspring of the Lake Patzcuaro Salamander and the Vietnamese Crocodile Newt have also been distributed.

The population management is one of the tricky tasks of conservation breeding. On the one hand, it is important to repeatedly achieve offspring in as many husbandries as possible so that breeders remain in practice and the animals show that they are capable of reproduction and the conditions are right. At the same time, the CC population must remain demographically healthy and as genetically diverse as possible. This is only possible if some of the offspring bred leave the programme again. It remains a constant tinkering and balancing act – and therefore an ongoing challenge for our species managers.

Animal population overview 1 May 2025

(You can scroll horizontally in the table.)

| Scientific name | Engl. name | Animals total (m/f/u) | Keepers total | Deaths 11/2024 – 04/2025 (m/f/u) | External delivery 11/2024 – 04/2025 | New offspring 11/2024 – 04/2025 | External arrivals 11/2024 – 04/2025 | Aim (animals, keepers) | status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibien | |||||||||

| Agalychnis lemur | Lemur Leaf Frog | 35 (17,9,9) | 7 | 7 (1,2,4) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 225, 40 | 17 % |

| Alytes muletensis | Mallorcan Midwife Toad | 767 (73,89,605) | 59 | 255 (8,1,236) | 341 | 154 | 0 | 425, 53 | 100 % |

| Ambystoma andersoni | Anderson’s Salamander | 101 (16,20,65) | 15 | 40 (0,3,37) | 0 | 19 | 13 | 225, 40 | 41 % |

| Ambystoma dumerilii | Lake Patzcuaro Salamander | 208 (62,55,91) | 29 | 17 (5,2,10) | 21 | 22 | 0 | 225, 40 | 82 % |

| Atelopus balios | Rio Pescado Stubfoot Toad | 208 (21,30,157) | 21 | 106 (2,1,103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225, 32 | 96 % |

| Bombina orientalis | Oriental fire-bellied Toad | 367 (42,31,294) | 26 | 33 (1,0,32) | 0 | 64 | 0 | 225, 60 | 72 % |

| Ecnomiohyla valancifer | San Martín Fringe-limbed Treefrog | 26 (0,0,26) | 2 | 6 (0,0,6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225, 56 | 8 % |

| Epipedobates tricolor | Phantasmal Poison Frog | 34 (5,1,28) | 4 | 7 (1,2,4) | 0 | 0 | 8 | 320, 45 | 10 % |

| Gastrotheca lojana | Loja Marsupial Frog | 11 (5,6,0) | 3 | 1 (0,1,0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225, 38 | 6 % |

| Ingerophrynus galeatus | Bony-headed Toad | 89 (24,8,57) | 8 | 53 (1,1,51) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225, 40 | 30 % |

| Minyobates steyermarki | Demonic Poison Frog | 32 (9,13,10) | 7 | 6 (0,0,6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 110, 20 | 32 % |

| Odontobatrachus smithi | Smith's Toothed Frog | 19 (0,0,19) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225, 38 | 7 % |

| Phyllobates terribilis | Golden Poison Frog | 97 (12,8,77) | 12 | 11 (4,2,5) | 0 | 3 | 5 | 225, 70 | 30 % |

| Salamandra sal. almanzoris | Almanzor Fire Salamander | 31 (12,8,11) | 8 | 4 (4,0,0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185, 30 | 22 % |

| Salamandra salamandra (D) | Fire Salamander | 301 (60,43,198) | 35 | 10 (1,0,9) | 0 | 49 | 44 | 330, 90 | 65 % |

| Staurois parvus | Lesser Rock Skipper | 213 (50,43,120) | 3 | 4 (0,0,4) | 0 | 10 | 20 | 500, 10 | 36 % |

| Telmatobius culeus | Titicaca Water Frog | 73 (15,19,39) | 8 | 1 (0,0,1) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 225, 45 | 25 % |

| Tylototriton vietnamensis | Vietnamese Crocodile Newt | 140 (32,56,52) | 29 | 24 (10,8,6) | 23 | 0 | 18 | 185, 30 | 86 % |

| Tylototriton ziegleri | Ziegler’s Crocodile Newt | 55 (15,16,24) | 12 | 3 (1,0,2) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 185, 30 | 35 % |

| Fische | |||||||||

| Bedotia madagascariensis | Madagascar Rainbowfish | 159 (48,41,70) | 15 | 18 (6,3,9) | 0 | 47 | 0 | 192, 16 | 88 % |

| Cyprinodon veronicae | Charco Palma Pupfish | 181 (59,60,62) | 5 | 16 (0,0,16) | 0 | 25 | 0 | 225, 15 | 57 % |

| Limia islai | Tiger Limia | 387 (67,77,243) | 12 | 113 (2,2,109) | 0 | 186 | 0 | 2000, 20 | 40 % |

| Parosphromenus bintan | Bintan Gourami | 41 (9,9,23) | 4 | 7 (5,2,0) | 0 | 0 | 19 | 100, 15 | 34 % |

| Ptychochromis insolitus | Mangarahara Cichlid | 483 (47,60,376) | 15 | 11 (0,0,11) | 4 | 170 | 0 | 192, 16 | 97 % |

| Ptychochromis loisellei | Loiselle’s Ptycho | 237 (6,6,225) | 9 | 131 (1,0,130) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 192, 16 | 78 % |

| Ptychochromis oligacanthus | Nosy Be Cichlid | 387 (31,31,325) | 6 | 358 (3,3,352) | 0 | 10 | 0 | 192, 16 | 69 % |

| Reptilien | |||||||||

| Cuora cyclornata | Vietnamese Three-striped Box Turtle | 8 (1,2,5) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100, 50 | 8 % |

| Goniurosaurus huuliensis | Huu Lien Tiger Gecko | 8 (4,4,0) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 110, 55 | 7 % |

| Phelsuma guimbeaui | Mauritius Lowland Foerst Day Gecko | 25 (6,15,4) | 7 | 1 (0,1,0) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 110, 55 | 18 % |

| Rhampholeon acuminatus | Nguru Spiny Pygmy Chameleon | 13 (6,7,0) | 3 | 8 (6,2,0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 215, 36 | 7 % |

| Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia | San Francisco Garter Snake | 19 (12,7,0) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 110, 28 | 21 % |

m: male, w: female, u: undetermined sex * Status = mean value of the percentage of the target number of keepers already achieved and the target number of animals